The Spies Next Door

By Matt Mendelsohn

First published in Washingtonian Magazine, August, 2014

“We can neither confirm or deny that this is our first tweet.” The CIA’s first-ever tweet, June 6, 2014.

The two newspapers had been switched, like every other morning, and I knew within seconds there would be a signal telling me if the mission had been a success. Some agents opt for an upside-down flag in a window, others for a chalk mark on a park bench—tradecraft, we call it—but I was dealing with a particularly old school spook. We had a routine down by now, me and her, and that’s why my daily walks always involved a very specific act: one copy of the Washington Post traded for another. Each sunrise, I'd tiptoe onto her lawn and look around quickly to see if I was being watched. With one swift motion I'd reach down and pick up the target, replacing it quickly with the fresh paper nestled under my arm.

This day, no different. The swap made, I beat a hasty retreat back to the street and positioned myself neatly in the shadow of an enormous tree. For a few seconds, nothing. Then in a flash, almost imperceptible to someone not in our line of work, came the sign.

The venetian blinds swayed ever so slightly.

She had seen.

Failure. Every day a failure! Let me tell you something—when your six-month-old Golden Retriever puppy rips up the newspaper of your neighbor every single morning, and I mean rips with extreme predjudice, and you’re simply trying to do the right thing by replacing that shredded copy with an intact one of your own, take it from me: make sure the house isn’t owned by retired spies. They don’t miss a fucking thing.

Welcome to my neighborhood. All of us knew both Mr. and Mrs. Carlson spent their lives working for the Central Intelligence Agency. In my North Arlington, Virginia subdivision, it’s more of a question of who isn’t retired CIA. I mean, I'm not. I can’t even figure out how to unlock my car at six in the morning without it making two beeps loud enough to wake the whole block—but I do love a good story.

Rod and Pat Carlson had them by the boatload, no doubt, but they never told. At least not to me. Exceedingly reserved, the old couple had lived in the same small house since 1967 and rarely chit-chatted with us newcomers. Rod had a gaunt, Amish look about him, a modern-day Abe Lincoln. You expected to see him swinging an axe. Pat was a wisp, so frail I worried she’d get blown over on windy days. I’d be in line at Safeway and she’d suddenly appear behind me—very ghost-y but always very sweet, too. For years they lived a hundred feet from me and I never thought to ask what they did at the CIA.

Every block has a couple of homes where the lights go out earlier, where the sounds of crying babies subsided decades ago, and where kids don’t bother to try trick-or-treating. “Not that house, Jimmy, it’s dark!! They never answer the door!” Old neighbors. But when those houses contain retired spies, the ante jumps. Kids today would leap at the chance to play secret agent. Grown-ups, too, what with our cubicles and billable hours. Decades from now their stories, which could never be told when they were young and vibrant and, most of all, classified, will start to disappear.

Rod died in 2004 and for the next eight years Pat was on her own. I always made sure to shovel her walk after a snowstorm. She’d rarely ever come out, but I’d see the venetian blinds sway ever so slightly and knew she had appreciated it. That was her way. Only after Pat died in 2012 did I begin to realize what our block had lost.

As my own father was gravely ill, I couldn’t attend the memorial, though everyone said it was nice. “Her children were all there,” our mutual neighbor Kasey said. “In fact, one of them said something funny.”

“Oh, crap. Don’t tell me it had anything to do with Cooper ripping up her mom’s newspapers. I apologized years ago, I swear!”

“Nah,” said Kasey laughing. “What she said was this: ‘Now that mom and dad are both dead, there go the last two people who could have told you who killed JFK.’”

****

Arlington may not sound like Spy Town USA, but my street is a three minute drive to the main gate of the CIA. Those folks have to go somewhere after five o’clock. For sixteen years, I’ve craned my neck driving by that entrance, each time hoping to see something other than a disappearing road. Years ago, I remember, it was summer and a few of us were sitting around on the lawn trading stories. One neighbor told a story involving his days in the Coast Guard. I followed with the time I made three cross-country flights in a single day, one of those flights in a tanker accompanying a squadron of F-117 stealth fighters from Sacramento to Plattsburgh, New York in a KC-135. The stealth fighters were brand new in 1990, the Gulf War was looming, and I was working as a wire service photographer. For someone who hates to fly, it was a good day.

Until, that is, an older neighbor spoke up.

“Back when I was at the Agency…”

Boom. I knew my stealth story was DOA. Whatever the next words to come from his mouth, they would certainly be better than a flight in a KC-135. And they were.

“Back when I was at the Agency,” he said, “we once pulled a nuclear-armed Soviet submarine from the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.”

You did what? Who’s we? The U.S.? From where?!? I didn’t want to be the guy in the movie theater who asks a million questions before the title sequence has finished, but he had me from “Agency.” I had lived a house away from Rod and Pat Carlson and it never dawned on me to chat them up about their spy days. Now, a different neighbor was talking about recovering submarines from the bottom of the Pacific and I would not make the same mistake again.

Close your eyes and think back to the summer of 1974. President Nixon is inching closer and closer to resignation. Turkey has just invaded Cypress. The Cold War is still icy. You’re wearing bell bottom pants, every guy has a mustache and the transistor radio crackles out the hits of the day. Rock the boat, don’t rock the boat baby. Rock the boat, don’t tip the boat over. In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, some 1,500 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii, a huge commercial ship, the Hughes Glomar Explorer, bobs up and down. Is it a drill ship? A mining operation? Hard to tell, though whatever they’re doing isn’t very exciting. A hundred and fifty feet away, a Soviet tugboat, SB-10, bobs right along, watching. The mutual admiration goes on for two whole weeks. But time is relative. To really grasp the story my neighbor told that night you need more than two weeks.

More like six years. Because that’s when this story truly begins.

****

Dawn was still a few hours away on February 25, 1968 when the the ballistic missile submarine K-129 skimmed out of its berth at the Rybachiy Naval Base in Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula heading due south. With a crew of ninety-eight, a Ukrainian commander (yes, hard to fathom these days) and three 1-megaton nuclear warheads, her upcoming patrol would have been considered routine. And that’s pretty much how things went for the first two weeks.

Then, on March 11, most likely during a drill, an explosion. In those days the Soviets used liquid fueled rockets, a risky practice the U.S. Navy had abandoned. “Very nasty stuff,” someone will later explain to me, and nasty is exactly what results. K-129 loses propulsion, can’t blow ballast. First comes crush depth, then the bottom of the ocean. In a matter of seconds, 2,700 tons of steel capable of launching a nuclear attack on the United States turns instantly impotent, tumbling three miles out of control. At the bottom, wrapped inside her imploded, fire-ravaged hull are her codes and code books, those nuclear missiles and nuclear-tipped torpedoes, the Soviet technology of the time, and, most tragically of all, a crew of ninety-eight, men with names like Motovilov and Kostyushko and Chichkanov. All never to be heard from again.

But like time itself, never can be a relative term. For six long years, while K-129 slumbered, the Russians searched and agonized. The Americans just schemed. We found it and they didn’t, that’s the long and the short. And pretty quickly after the sinking, too. The Russians didn’t have a clue we knew, though that wasn’t much consolation to the American spy apparatus in those first months. We had found K-129, sure, but now what? It’s not as if you could recover it. No one in their right mind had ever thought about recovering something—anything—from that depth, and certainly not an enemy submarine, in a raging Cold War, and with the specter of a very real war should the Russians find out.

Perspective? Titanic lies at the relatively shallow depth of 12,500 feet. Malaysian Airlines flight 370 is presumed to be around 15,000 feet. But 17,000, in an era before GPS and before modern computing? Not a chance in Hell.

Not surprisingly, it was the U.S. Navy that had first crack. For a year the Navy kicked around plans that mostly involved floating things, one by way of massive balloons, but nothing stuck. That’s when the plan got handed off to the CIA, which, on the surface, had far less experience having to do with ships and water. But that's what makes this story so compelling. And unbelievable. One day a Russian sub sinks in the pacific; the next year a bunch of me who had been working on satellites and spy planes suddenly started becoming experts in all things marine. Just like that.

Working at the Agency at the time was a young man named Dave Sharp. He was recruited out of college and had never even been on a boat. His career was headed for the skies, not the seas. After working on the Bay of Pigs, Sharp transferred to the U2 program, and from there it was on to Area 51 and the SR-71 Blackbird. Water was not in his cards.

Meanwhile in Houston, Texas, Sherman Wetmore was busy designing commercial drill ships for a company called Global Marine. Sunken submarines and espionage weren’t on his radar, either, but oil sure was.

And in California, far from his Brooklyn roots, Ray Feldman was hard at work at Lockheed on another aerial spy program called Corona. He loved his work, but he also loved the fact that his California job got him away from his New York in-laws.

Three men who had never met. Yet one explosion in a submarine thousands of miles away would change their lives forever; one explosion that propelled the CIA and its contractors into crash courses in ocean dynamics and mechanical engineering, of lift and heave, not to mention a degree of operational security perhaps greater than anything ever attempted in history.

All because the brain trust at Sherman Wetmore’s drilling company convinced Dave Sharp’s superiors at the CIA that they could do the unthinkable: lift a four million pound piece of a submarine from three miles beneath the surface, and do it without the Soviets knowing what was happening. Broad daylight, baby.

It makes you wonder: What if ARGO was the easy mission? What if, with all due respect, getting some embassy staff through the Iranian airport was not the most ambitious accomplishment in the long and secret history of the CIA, no matter what the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences says? It doesn’t even come close.

****

“Are subs okay?”

Dave Sharp is emailing me before our first meeting. He’s politely asking about lunch options but the irony isn’t lost. A few days later we’re sitting in the kitchen of his Annapolis home.

“Those are ospreys,” he says looking up at the sky. “Sea hawks. They’re all over the place.” Trim, with a head of white hair, Sharp, now 80, is a soft-spoken man who clearly enjoys spending his retirement on the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. His backyard looks out over the South River, and a kayak and a Boston Whaler sit moored a few feet away. Age has cleaned him up nicely. Back in the seventies, his first wife used to joke that he looked like Wolfman Jack, long hair and a mustache covering what he calls his markers (“your ears are just like a fingerprint”), and a code name, Dave Schoals, covering his tracks.

You never know what CIA folks are supposed to look like—they’re just mowing the grass like I used to see my neighbor Rod Carlson doing—and Dave Sharp doesn’t seem particularly Mission Impossible-y to me. Mostly just exceedingly polite. But he has two things going for him, one of which puts him in a bit of rarified air: he was on the ground floor of project AZORIAN, the code name the Agency bestowed upon its nascent and somewhat preposterous plan to recover K-129; and he is the only CIA employee ever given a green light to write a book about it.

In short order, the CIA team did what the Navy did not: it sought out the advice of outside experts, and the experts in these matters were in the business of drilling. Global Marine had a long history of building commercial drill ships and they wasted no time poking holes in the ideas the Navy had come up with—the “rockets, air-filled pontoons, pentane barges, the works,” as Sharp writes in “The CIA’s Greatest Covert Operation.”

“If we had any marine engineering experience,” he says, “we would have never dared to take on the job.”

As mementos go, the three keepsakes Dave Sharp has stashed in a closet in his Annapolis, Maryland home seem at first a tad underwhelming, not exactly Kane’s Rosebud or Yuri’s balalaika. They’re not displayed on a shelf, as you might, say, a foul ball caught at the stadium, and collectively they don’t appear to be worth very much, if anything. The first item Sharp still has is a coffee mug. It bears no markings, no “Town Bagel, Huntington” or “East End Diner” to distinguish it from any other mug you’ve ever seen. Just a plain old, white ceramic coffee mug.

“It’s heavier than most,” Sharp explains. “They’re built a little stronger to resist the swells of the sea.”

Dave Sharp is not a man of many words but not because he’s trying to be cagey. He simply thinks carefully before speaking. The next artifact he’s hung on to might be even duller than the first: a white construction hard hat, about as generic as they come. There’s no company name, which is probably not surprising. On the front it reads “Dave Schoals.”

It’s the third piece that starts to get your heart pumping. It’s a plaque, the kind given to model employees at companies around the world every day. “Server of the Month,” “President’s Club Top Seller,” that kind of thing. But Dave Sharp’s plaque doesn’t actually say anything. Not a single word. On it is a kind of abstract artwork done in metal. If you stare hard enough, you can start to see the shape of a hammer and sickle. But it’s what’s inside that hammer and sickle that’s truly the prize.

There’s a bicycle race out west called the Leadville 100. Leadville, Colorado is the highest incorporated town in America, at 10,000 feet, and if you finish the race, all 100 miles at that crazy altitude, you know what they give you? A belt buckle. No money, no endorsements, no fame. Just a belt buckle. But you wear that belt buckle and you don’t need to say a word. People know.

Kind of like this mysterious plaque Sharp has. Because mounted inside that hammer and sickle-ish looking design is something only a few people on this planet would ever understand: a one inch by one inch piece of steel, basically the size of your thumb.

That’s it, you ask? That’s it. A postage stamp-sized souvenir. No markings, no trite inscription about teamwork or success. You might as well have be staring at a moon rock. Then again, outside of a moon rock, Dave Sharp’s tiny square of steel may be just as rare, perhaps the most exclusive “attaboy” ever bestowed by an employer to an employee. Because what Sharp did in utter secrecy for six years to earn this gift—becoming Dave Shoals each and every morning, lying to his family and friends, puking his guts out on the swells of the Pacific Ocean, that heavy coffee cup in hand—probably qualifies as the second-greatest engineering project of the twentieth century after the moon shot. The one major difference being of course that Neil Armstrong remains an American icon, while Dave Sharp isn’t even famous on his own block; that one event lives on in glory and movies and books and history while the other continues to fly beneath the radar screen of obscurity. The Apollo program left some things behind on the surface of the moon and Dave Sharp’s team left something at the bottom of the sea. But he’s got this.

“That’s all I have” Sharp says of the 1” x 1” piece of submarine hull. "That's all that remains."

****

Where do they even begin? After the Navy folded its hand, the CIA began looking at its contractors for a partner who could help with the technology, as well as maintain operational secrecy. The Global Marine team counseling the CIA was headed by Curtis Crooke, its vice-president for technology, and John Graham, its chief shipbuilding architect. Sherm Wetmore worked under them. Sharp relates a hysterical story in his book of Graham and Crooke coming to Langley for their first visit and being given explicit instructions to sign their hotel register as if they worked for the bogus “Graham Pharmaceuticals,” which would have been great but for the fact neither man knew how to spell the word “pharmaceuticals.” Remember: these were shipbuilders, not drug manufacturers. The Agency entrusts Global Marine with by far the largest piece of the puzzle—overseeing the construction, from scratch, of a massive ship capable of pulling K-129 from the sea floor. Enter, the Hughes Glomar Explorer.

And as if that task isn’t big enough, the folks at Global Marine suggest an even bolder—and more intangible—facet of the fledgling covert mission: creating a cover story that involves a fake ocean mineral mining ship. The CIA responds enthusiastically and even ups the ante: how about getting the reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes and his Hughes Tool Company to sign on as its cover story? Glomar could pretend to be a ship looking for mineral deposits—manganese nodules, they’re called—on the ocean floor. “The CIA had, after lots of study and discussion, selected ocean mining as the best cover story to explain the recovery activities,” Dave Sharp says.

“The idea of a government prime contractor just didn’t make sense to us, though. None of the usual government suspects were viable. We felt we had to have a commercial contractor…who could mislead the public about the nature of its work without lying to the stockholders.”

Ray Feldman, now 81, remembers thinking a little respite from his satellite ventures sounded ever so attractive. A cruise. “Oh, sounds greaaaaaat!” he thought of the offer to work on a Howard Hughes mining venture. “A real commercial program. Get away from all this black ops stuff!” Feldman talks like a much younger man and his memory is as hysterical as it is perfect. “I was bearded then. I had a lot of hair. I was trying to be a hippie, trying to disguise. Then they called me in and said, ‘Here’s what we’re really doing.’"

The plan to use Hughes as a cover still makes him giddy. “That was the icing on the cake, getting Howard Hughes involved ‘cause he was known to do all sorts of wild stuff and he owned his company outright. Didn't have to answer to stock holders. And he was weird. Everyone knew he was weird!”

Hughes’ “weirdness” gives the CIA and its partners Global Marine and Lockheed just the breathing room they need to be able to commission a commercial mining ship without anyone thinking too much about it. You can’t build a ship that size in a vacuum, remember. It’s out in the open. “Our mission was to build the ship and put it all together,” Sherm Wetmore says of his firm’s role. “Provide a crew, make sure it got down and came back up.” But retrieving K-129 presents a unique problem from the start, unlike anything else ever attempted—and you can take that all the way back to the Phoenicians. There’s a mangled, strewn-out submarine at the bottom of the ocean and it’s not wrapped in a neat and tidy package or position. It’s embedded in the sediment of the ocean floor.

“It's like trying to pick up a piece of jello,” says Wetmore. “You go down with a fork and maybe if it's cold enough, the jello will stay together. Maybe. It’s almost an impossible task to pick up something when you don’t really know what you’re trying to pick up.”

Global Marine focuses the CIA in one direction: a grunt lift from three miles up.

Imagine for a moment you’re at a gym, about to perform a dead lift. You reach down towards the floor, grab a barbell loaded with, say, 275 pounds, and in one smooth motion you stand up. That’s it. Put that same barbell aboard a rowboat in a choppy lake and try to do the same thing. Your balance is instantly challenged by various forces, the most obvious being that your standing in a flimsy, rocking boat. Now, attach seventeen million pounds of weight in the form of steel pipe and try to do the same kind of lift from a depth of 16,700 feet, all while the seas of the Pacific Ocean swell.

With all this in mind, a plan began to take shape. A fake ocean mining ship. All that steel pipe, pieced together in pairs of thirty-foot sections, known as the "pipe string." A mammoth claw—henceforth known as the capture vehicle, the "CV" or “Clementine”—that would scoop the Russian sub from the bottom and cradle it on its journey up. And, finally, a massive “moon pool” located in the belly of the Glomar Explorer, accessible by way of huge doors on the ship’s bottom, that gets drained once the sub is safely inside. If you think spy stories involve miniature cameras and trench coats, try a 63,000-ton ship on for size.

****

“It’s what we called the Three Body Problem,” Dave Sharp explains. “You’ve got a surface ship, you’ve got a pipe string hanging down, and then you’ve got a capture vehicle waiting on the bottom of it. And how do those things react and move together in different sea states? You're presented with all of these issues that have nothing to do with the submarine at the bottom of the sea. You're just dealing with how do you keep a ship stable with that much water within itself. And trying to make the system work. Trying to see if we can operate a heavy lift system that lowers and raises pipe in the open ocean. We'd never done that before.”

Sharp writes about all of this in his book, though what’s interesting is not necessarily what got published but how long it took him to do it. When he initially submitted his manuscript to the CIA’s publication review board, it came back with every single word redacted. Every one. “It was hostile. There were some suggestions that what I was doing was treasonous.” He had stepped onto a hornet’s nest. “One of my good friends, a security officer on the mission, was adamant that nothing should be published. Still is.” Sharp smiles.

“Although he bought about 40 copies of my book to give to his friends.”

Sharp is convinced larger issues are at work. “I’ve speculated that perhaps the Agency has this feeling like they want to have one program that is never declassified. And they want AZORIAN to be that one.”

It makes you think. Project AZORIAN took place from 1969 to 1974. What on earth are they still afraid of?

****

A few months after my neighbor Pat passed away in 2012, her children put the house up of sale and we did what neighbors do at open houses: we snooped. My wife and I walk down the block, all of a few steps, and enter Rod and Pat’s former home. It’s totally empty, save for a piano the movers hadn’t gotten out yet. A realtor welcomes us and asks us to sign in. Maybe we should make up Russian sounding names like Olga and Boris, my wife Maya jokes.

As she goes up to look at the bedrooms, I wander into the den, where a few straggler books linger on the mostly empty shelves: some gardening books, nothing much else of note. That’s when I see it, in a bronze dust jacket, sticking out like a sore thumb: “The Secret History of the CIA” by Joseph J. Trento.

As other potential home buyers stroll by, I peruse the index to see if Rod is listed. After that whole who-killed-JFK remark from his daughter, I found myself suddenly more curious about what my neighbor actually had done at the CIA. Was he a desk guy? A field agent? Did he ever kill someone with an exploding pen?

The index lists a “Rodney Carlton,” with a “t,” on page 247. Mildly dejected his name is misspelled, I still feel a sense of excitement. I skip backwards through the 500 or so pages, expecting to find a sentence or two containing the name of the man I only knew when I’d see him cleaning his gutters. Instead, I stumble headfirst into the mother lode. Rod Carlson is there alright, but not just in the publisher’s printed words. No—Rod has scribbled notes all over the pages. In a book about spies, my neighbor the spy had taken the time to correct the record. Repeatedly!

“Maya,” I whisper loudly. “Come here, quick.”

“What is it?”

“Um, look at this. Act nonchalant.” We both start reading on page 246.

“Penkovsky passed more film in Moscow at the Queen’s Birthday reception at the British Embassy and at a Fourth of July celebration at the American Embassy.” I have know clue who Penkovsky is but already I’m liking the Queen part. And Moscow, too! Then I see what Rod has written in the margin. “Wrong. No pass then.” Hmmm.

I skim further down: “At this point, the British turned the operation over to the CIA out of fear of it being further compromised.” Rod had underlined that sentence. “Wrong!” he had scrawled.

Down even further: “Penkovsky’s last attempt to deliver film at a U.S. Embassy reception on September 5 failed because he did not recognize [State Department security officer John] Aybidian in the crowd.” This time Rod goes a bit ballistic. “TOTALLY WRONG!! Aybidian was long gone. P and I met but decided not to try a pass.”

P and I met! He calls him “P”! I flip back a page or two so I can see what year we’re talking. There it is—1962. I flip backwards again, still trying to get the larger picture, and find this: “Penkovsky warned his debriefers that Khruschhev was bound and determined to win his battle with the West by rattling nuclear weapons.” And this: “Penkovsky’s photographs caused hearts to swoon at the CIA. The pictures delivered across-the-board intelligence that Penkovsky had access to all sorts of Soviet military secrets.”

Here I am, at an open house, surrounded by folks looking for Corian® countertops and hardwood floors, and instead I’m reading furiously about spies in Moscow in ‘62. The overall finally emerges. It wasn’t all that difficult to grasp, especially when one sentence contains “Penkovsky’s sentence was death by firing squad” and the next chapter begins on an island south of Florida.

My neighbor Rod was at the genesis of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Passing film with one of the most infamous double agents in history!

My mind is racing in the best, most excited kind of way. I want to get home and look up all this stuff up but there's a more pressing issue.

“Maya, um, how do you steal a book about spies from a dead spy’s house?”

She laughs. “Are you serious?”

“Yes I’m serious. This is going to be thrown out with the trash on Monday. We need to liberate it. Now!!”

“You’re the chattiest Long Island Jew I know. You couldn’t steal anything! They’d torture you and you’d spill the beans in all of three seconds.”

Well, she had a point but I was not going to let Mr. Trento’s history, with all of Rod Carlson’s first-person annotations, get tossed into a landfill. “Look,” my wife says, “you stay here. I’ll go distract the realtor with some questions about the asking price and then you can just put it under your sweater.”

Five minutes later, she returns and I’m still there. She’s right. I’d make a terrible spy.

*\*\*

--

By the end of March, 1974, six years after K-129’s sinking, the freshly built Glomar Explorer was ready to go. She had taken two years to complete—pretty quick, all things considered. “We’ve had houses in this neighborhood take longer than that,” Dave Sharp says, laughing.

First, though, a quick stop to pick up one very important item: Clementine, the capture vehicle—a four million pound addition to its hold. Built secretly within a immense barge in Long Beach, CA, both claw and barge are towed to Catalina Island and purposely sunk in shallow water, in plain view of boaters and sunbathers. It takes an entire day.

“It was a job to keep the boaters away,” Dave Sharp remembers. “They all wanted to be up close to see what was going on. We had little power boats with security warning people ‘Don’t get close! Danger!’ We didn’t want anybody diving under the ship and seeing what was really being put into the ship.” Then, under the cover of darkness, Glomar positions itself over the submerged barge. Retractable covers and doors on both are opened and in one very secret coupling maneuver, the Glomar Explorer becomes a modern day pirate ship with a mission..

On June 20, 1974, Glomar leaves her berth in Long Beach for good. By the Fourth of July, she was in place, floating over the target, about 1,500 miles from Hawaii. And there's company. For two weeks the Soviet salvage ship SB-10 sits watching from a short distance—monitoring Glomar’s every move, aggressively circling on occasion. Glomar isn't doing anything remotely suspicious, of course, but when you’re out on the high seas of the Pacific Ocean acting as a kind of all-purpose floating service station to Russian navy vessels along a familiar sea corridor, the mere presence of another ship, particularly an American one, becomes a bit of a welcome distraction. So the Russians watch.

At first, an actual Soviet missile range tracking ship, Chazhma, decked out with sophisticated radar, is sent to sniff around. But in time, needing to return home for supplies, Chazhma sends a warm “I wish you the best” message to Glomar and is replaced by the decidedly low-rent tugboat SB-10. It’s like swapping a Formula One pit crew for a bunch of guys from Jimmy’s Garage. How much could they really have known about what they were looking at anyway?

SB-10 believed what they were led to believe: Glomar was a monument to to the wealth and eccentricity of its owner, Howard Hughes, and his desire to plumb the depths of the ocean floor for untapped and profitable mineral deposits. Above deck, every half an hour the ship’s transfer crane would pick up another “double,” those connected thirty-foot sections of steel pipe, and add it to the ever-lengthening string. “Like a giant praying mantis,” Ray Feldman recalls.

The piece of K-129 they’re after—the “target object” in the parlance of the mission—extends from the tip of the sub’s bow to the aft end of the sail. Despite daily hiccups, things are moving along. By the beginning of August, the tines of the capture vehicle are being been forced into the soil around K-129. But the ocean floor is harder than the team counted on and a million or two extra pounds of pipe is added to the string, pushing the capture vehicle lower and forcing its claws deeper into the dirt.

A few hours later, the CV’s breakout legs, designed to remain at the bottom like the lower portion of the Lunar Module, give the the initial push it needs to break free of the sand. And in a declaration more suited for that recently shuttered Apollo moon program, Sherm Wetmore announces “We have liftoff,” and the long, reverse process of pulling all that pipe back begins.

--

It’s worth noting the magnitude of it all. Clementine weighs four million pounds. So does the section of K-129. The pipe string adds nine million more pounds to the mix. All together, seventeen million pounds, six years and $500 million dollars (almost $3 billion today) of unparalleled espionage by the Central Intelligence Agency hanging from a ship. And the whole awkward configuration is stretched so much like a rubber band that the pipe string is forty feet longer than when it all started. Forty feet. We’re talking steel. Yet it works. For the first time since March, 1968, K-129, filled with a treasure trove as well as skeletal remains, begins to move.

Then, trouble. The first sign something was amiss came early in the morning on August 1, 1974, though to look at Glomar Explorer’s original log books, which Dave Sharp still has, you’d never know it. All it says, cryptically, is “0659 heave comp at top of stroke.” You could call it this mission’s “Houston, we have a problem.”

It’s not easy being a fake ocean mining ship. More than anything, the Glomar crew worried about being boarded some day by their Soviet watchers. The ships’s logs had to maintain the cover story, so they were written as if an actual deep sea mining venture was underway. Sift through the endless entries written in dull engineering speak and you’ll never once see mention of a sub or Russia or missiles.

The "heave comp," or heave compensator, the part of Glomar’s heavy lift system designed to make adjustments for the swells of the sea, had been problematic from the start. Three days earlier, on August 1, moments after Sherm Wetmore said “We have liftoff,” the compensator had broken down. As the crew worked to repair it over the next twenty hours, the capture vehicle containing the submarine was temporarily re-lowered back onto the ocean bottom. It seemed like a fairly innocent step to take at the time, just a hiccup in what had seemed like a promising start. In hindsight, it may have been the whole mission.

“It was not designed to take that weight,” Ray Feldman says. He clarifies: “It was designed to take weight but not that kind of compression, where you’re actually pushing down on the soil. It was not intended to do that.”

Though subsequent postmortems would debate whether the right kind of steel was used for the capture vehicle, K-129’s fate may have been sealed right then. After the heave compensator was fixed, pipe pulling resumed. The Russian submarine was up some 7,000 feet when the crew of Glomar felt a shudder. “I thought maybe we had a another heave compensator failure,” Dave Sharp says. “I went up to the control center and everything looked normal there. They’re all still looking at the submarine and the claws, and I said, ‘You know, you sure you got all the targets there?’

“Yeah, everything’s fine,” came the response. And then: “Oh, wait a minute, we haven’t refreshed the closed-circuit TV.”

“They were looking at old images,” says Sharp, “They refreshed the closed-circuit images and…gone.”

In an instant, a big chunk of K-129, six years in the taking, tumbled through the tines back to the ocean floor.

And that’s not all.

The sling-shot effect of losing all that weight threatened to send the pipe string shooting up through the ship. “The shock of the weight,” say Ray Feldman, “and the heave compensator being bounced up to the very top with such force. You know, the ship had no keel. Normally, a keel is a key structural member in the ship, so all the structure had to be in the wing walls. The ship had a big hole in it.”

Dave Sharp immediately knew it was a catastrophic loss. “My best guess is the tines were continuing to leak, so they were changing position, and you also had a continuing motion, some motion up and down, cyclical motion as we were rising, just from heave of the ship that gets transmitted down the string, and it just, something gave. One gave, then the others gave, and it was like a zipper. We couldn’t even tell what the stresses were by this time, because the instrumentation wasn’t working.”

“And then it fell away.”

*\*\*

--

The CIA is in a cheery mood on a March morning, which is a bit off-putting.

I dial the main switchboard to ask if the Agency is planning any special AZORIAN commemoration this summer and I’m connected to a very helpful woman named Lisa in the media department. “I’m so glad you called!” Lisa says, which is about the last thing you expect to hear when you phone the CIA. Maybe it was a slow day. Truth be told, I was kind of hoping for a Glomar Response.

It seems hard to fathom that a ship known for hoisting a Soviet ballistic missile submarine could be famous for anything other than that, but Glomar is special. When the first stories leaked out in 1975, a feeding frenzy ensued. One journalist filed a Freedom of Information request seeking any materials related to contracts the CIA entered into during the construction of the Glomar Explorer. Needless to say, she was rebuffed, but it’s how she was rebuffed that still resonates.

The Agency responded by saying…wait for it…that it could neither confirm nor deny the existence of such materials. There’s a first time for everything. The phrase has become such a staple—not just for Agency lawyers but teens avoiding prying questions from mom and dad— that the CIA chose to make light of it when it entered the Twitterverse this June. That so many people reveled in the tweet while not understanding its origins is testament to the continued secrecy surrounding AZORIAN four decades later. Even today, the true end of the tale is top secret.

“That was the position the Agency took after the mission,” Dave Sharp says. “They realized that all these questions were coming in through the Freedom of Information Act, asking ‘I want all the information you’ve got on missiles that may have been recovered on that submarine.’ And they said, you know, we don’t want to deny that we got any missiles. That would tell the Soviets that we didn’t recover any missiles. On the other hand, they can’t say we did get missiles. So they developed the Glomar Response, which left the Soviets in a position where they’d say, ‘Well, shit, we can’t take a chance. We’re gonna have to change the codes, change the equipment, we’re gonna have to change our missiles.’”

Prying into another nation’s sovereign property, particularly one with ninety-eight dead sailors inside, was prickly. “I have a feeling, just a feeling and no evidence,” Sherm Wetmore says, “that it was kind of against international law to go poking around some other navy’s remains. I think somebody would take a dim view of that. I’ll bet it had to have been a big embarrassment to the Russians—the Russian Navy and the Russian intelligence.”

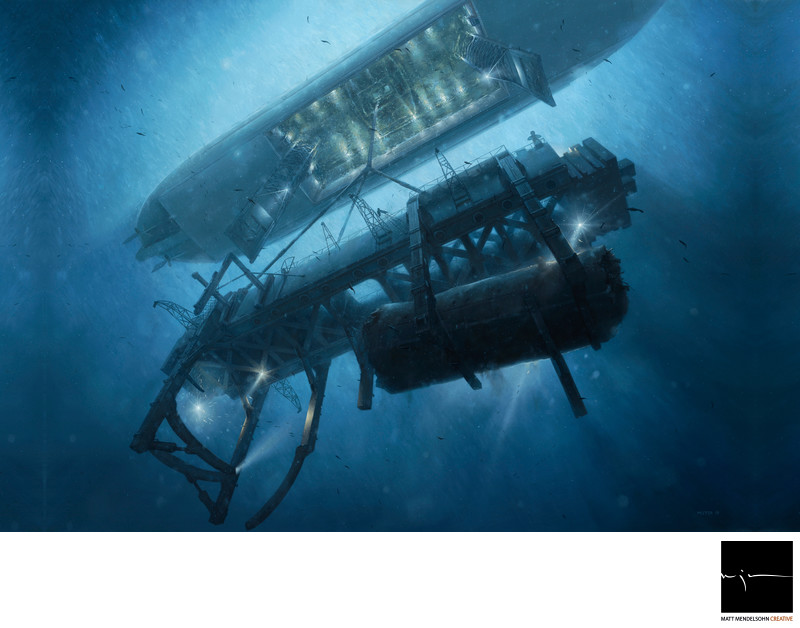

I think of these things a few weeks after my chat with Lisa. She’s set up an meeting with David Robarge, the CIA’s chief historian, and Toni Hiley, its museum curator, and in April we’re all staring at a beautiful 48” x 38” painting hanging in a corridor in Langley. (Finally I get to go inside the CIA and instead of exploding pens I’m looking at art.) Drawn in deep blue hues, the painting shows a crumpled submarine resting inside a huge claw that is attached to a string of pipe. “We had very little in the way of resource material that we could give the artist,” Hiley says. “I had maybe seven or eight line drawings.”

The eerily beautiful scene is depicted from beneath the action and you quickly realize this might be as good as it ever gets for Glomar and K-129. There are no existing photographs of this moment in history, just this one canvas hanging on a wall in a corridor that most Americans will never get to see. An hour earlier, Robarge, the historian, had been explaining the Agency’s historical perspective and his words are prescient as we gaze upon the secret artwork.

“The more the American public appreciate our successes and our failures, the challenges that we face, the complexities of the world as we address it throughout our history, they’ll have a much better appreciation for the work we do. Maybe in the long term it will have a beneficial effect on the public perception of us. That we’re not a bunch of evil geniuses or incompetent dolts, which are the polarities of the perception. And that’s it’s not a mix of the two, either, because both are wrong. It’s something else in the middle, just a lot of hard working intelligence people trying to approach complicated problems like ‘What about this submarine?’ in innovative and creative ways.”

Two-thirds of their haul might have fallen through the tines of the CV, but the men aboard Glomar knew they still had something on the line. After some demands from Langley that they start over and go back down and pick up the sub again—Dave Sharp had the unenviable job of telling his bosses that was not in the cards—the Glomar crew continued pulling pipe up. With each section of the string removed, their haul moved closer to the ship. That ragtag crew aboard the Soviet tug SB-10? A hundred fifty feet away, clueless. But it was getting harder to hide. The closer the remains (of the remains) of K-129 got to the underside of Glomar, the more she began to burp up bits and pieces of debris, the occasional diesel fuel can.

Her innards, stirred and shaken, were beginning to ooze out. The crew of Glomar is on edge. Are the folks aboard SB-10 seeing this debris? Not a chance. With their own lost submarine literally right under its nose, SB-10 decided it had seen enough of the monotonous (and utterly fictitious) “deep ocean mining operation” across the bow. Time to go home, they decided. As the two ships pass close by for the final time, the crew of the SB-10 renders a salute to their American counterparts: they drop their pants and moon, an act quickly reciprocated by the men aboard Glomar.

“The Soviets cheered and blew their whistle and took off across the horizon,” Dave Sharp tells me, and he was there too. “We never saw ‘em again.”

*\*\*

--

I’m watching kids play hockey at a local rink but my mind is pondering crush depth

instead.

“What are you reading that book for?” a fellow parent sitting next to me asks after

seeing my copy of Dave Sharp’s book. “You know I’m a submarine commander, right?”

Actually I didn’t but I jump at the chance to chat and before long sketches of missile tubes are being

drawn on napkins. I can’t help thinking about the crew of K-129, the one piece in the AZORIAN

equation which tends to get a little lost. Crews of secret operations sadly die without fanfare.

“The mourning happens at the personal level, not the institutional level,” the CIA’s historian

lamented to me once and I see his point. How can you acknowledge a death when you can’t

acknowledge a mission? Still, I wonder. What does a crew think about when faced with a sinking

sub? Is it like Malaysian Airlines Flight 370--a fleeting moment of terror and then a painless,

unconscious descent? When you scan the list of the 98 men aboard K-129 nothing much pops

out. Well, maybe one thing. The crew is almost exclusively Russian with three curious

exceptions, and all three occupy the very top three slots on the list. The commanding officer,

Vladimir Ivanovich Kobzar, and the deputy commander for political affairs, Fedor

Yermolayevich Lobas, are both Ukrainians, and the executive officer, Aleksandr Mikhaylovich

Zhuravin, is listed as Jewish. If for no other reason it brings to mind the spiraling reemergence of

the Cold War in the past few months and Russia’s incursion into Ukraine. The Soviet Union

that’s represented on the manifest, one where a Ukrainian could command a Soviet sub, is no

more, that’s for certain.

“I’ve spent five years of my life underwater if you add up all the days,” my commander

parent tells me later. (He requests that I not identify him.) “You want to know what we think

about? There are two things that scare us. The first would be a flooding casualty, and there are

very specific actions you take to secure all of the water penetrations, all of the sea water systems,

shut all of the valves. Normally that would take some kind of collision. You need to stop the

flooding and you need to restore propulsion immediately. The second one is a catastrophic fire. If

you have a catastrophic fire, you need to break the fire triangle. You need to eliminate the

oxygen, eliminate the fuel or eliminate the heat. If can’t eliminate the heat very quickly people

are going to start to expire.”

Ray Feldman is an engineer, not a submariner or a nuclear expert, but he agrees. “There’s

lots of theories still,” he says of the possible explosion inside the K-129’s missile tube. “My

personal theory is that there was a leak somehow. You know, the Soviet navy had a very poor

record. The U.S. Navy decided never use liquid fuel rockets on submarines. It immediately went

to solid rockets."

"The thing about the liquid fueled rockets that the Soviets used were that they

were made with a form of hydrazine, which is a fuel, and an oxidizer, which in most cases, is

some form of nitric acid. When they come in contact they ignite. You don't need an ignition

source, you don't need any complex spark plugging device. So if you get a leak in that stuff

you're in trouble. Very nasty stuff.”

“When everything went off, it breached the hull,” Feldman says. “Let's say a

submarine loses propulsion and it starts to go deeper and deeper and deeper. They can't blow

ballast, they can't make it rise, and so it goes deeper. And there’s something called crush depth.

Every submarine is rated for some sort of crush depth, when the hull will implode. Once that

happens, the instantaneous pressure inside reaches whatever it is outside. So lets say a sub's

crush depth is 1,000 feet. Well, its what about a half pound increase of pressure for every foot, so

at 1,000 feet the pressure outside is 500psi. Pretty high pressure.”

I ask my submarine commander parent what a crew member would be thinking when all

of these events are converging. “The awful part is the crew looking at those depth gauges,” he

says. “The ship is descending, they know they’re going to go through crush depth. Everyone

knows they’re going to die but there’s no suffering."

"It happens very fast.”

*\*\*

--

So what did they get? According to anyone who is willing to say anything, the answer is some version of “I’m not going to get into that too much.” Ray Feldman says it wasn’t any missiles, that’s for sure. “The Golf II sub had three missile tubes in the aft portion of the sail. It was obvious from the video from the capture vehicle, that two of the tubes furthest aft in K-129 were completely destroyed. It appeared that the last tube, which was damaged, might contain the warhead but not the entire missile. In any event, it was all moot since the entire sail, including remnants of the missile tubes, were lost when the sub broke apart on the way up.”

A few days after the Glomar pulled up its piece of K-129, Dave Sharp received a package aboard the ship. In it were the cremated remains of John Graham, the ship’s designer from Global Marine, who had died on shore while the mission was ongoing. “Just a plastic bag of ashes,” he says. “He decided he wanted to be buried from that ship, that it was the finest thing he felt he’d ever done in his career.” Sharp spread the ashes in the sea. A few days after that, a secret funeral service was held at sea for the six Russian seamen whose bodies were recovered inside the piece of K-129 which was recovered. Dave didn’t stick around for that though. He was already on his way back to Langley. Any slaps on the back when he returned for a job well done, I ask? “No, not that I recall…It was an operational failure.”

Sherm Wetmore is a bit more upbeat. “I don’t consider it a failure,” he says. “I don’t have any feeling of, ‘Oh god, we blew that.’ I think we did a good job. A magnificent failure, if you had to say failure.”

Ten years after my neighbor Rod Carlson passed away and three years after his wife Pat followed, I finally had a chance to speak with their daughter. Ingrid Carlson is 52 and still lives in Arlington. She’s an accountant. We laugh about my inability to “steal” the annotated CIA history book from her parent’s empty home. “You just walk out with it,” Ingrid says without hesitation, and I can see she’s got her father’s spy genes, not mine. (My neighbor Kasey called a few days after that open house. “I got it!” she said. “How?!?” I asked. “Through the basement window?” “No. I asked the realtor if I could have it,” she says, and I think oldest trick in the book.)

“I guess dad told us when I was in high school,” she says of her father’s vocation. “But I have to say that it went over my shoulders. When you’re that age you’re only worried about what’s going on in your own life. I know I didn’t understand the implications of it. Frankly, when you grow up in that kind of environment, everybody you know has parents who did things you didn’t know about. It just seemed so normal. I didn't think anything about it until I was much older.” She pauses for a second and adds, “Until you go out into the real world and realize how boring your job is.”

Her mother and father met at a blind date at the Agency, she tells me, and dad would dress up as Abe Lincoln for Halloween when she was little. Ingrid tells me a funny story (or maybe not) about those years in Moscow, when she was just one. “My sister Karen was born in Moscow. Mom was supposed to fly to Copenhagen to have the baby, because who would want to have a baby in a Moscow hospital back then?” But her mother went into labor early and that’s exactly what happened. So the spy who was secretly meeting with a soon-to-be executed informant was now dependent on a Soviet hospital to deliver his baby daughter. “I remember my dad saying they were leaving the hospital in the middle of the night and cars starting following them.”

A week after our conversation, I meet a former Agency employee who knew Rod well. “You know he was Oleg Penkovsky’s case officer, don’t you?” I shake my head yes. “He had a hard life. In those days the Soviets would bombard the embassy in Moscow with microwaves. That’s probably where his leukemia came from.”

And the dark days, too. When Aldrich Ames was unmasked as one of the most infamous traitors in American history, responsible for the loss of scores of foreign assets, her father was inconsolable. “They had been friends,” she says. “He felt incredibly betrayed. He wouldn’t even talk about it. ‘I thought I had a good judge of character,’ he would say over and over. ‘I guess I was wrong.’”

You always want to know more before it’s too late. I was just a neighbor and I wanted to know more. Ingrid was his daughter. “I wanted to ask him a lot more questions but he died so suddenly. Why didn’t I ask those??” She knows the answer to her own question. All the spy stories, all the danger, her entire youth—“It was just a blur to me. He was just my dad.”

With a promise to get together sometime, I hang up the phone with Ingrid and get ready to walk my dog past the house where her mom and dad once lived. I wonder if the curtains will still sway.

Sometimes moms and dads do pretty amazing things. Ray Feldman is moving to Napa, to be closer to his daughter. Feldman is getting to move up towards Napa to be closer to his daughter. “Maybe a month or two ago, she said, ‘You know, I don't think I’ve ever told you but I’ve always considered you my hero.’ She said that. That was kind of nice.”

Dave Sharp, now addicted to the water, still holds out hope that a movie studio will do for AZORIAN and Glomar what it did for Argo.“We have had some interest from a company called Mainline Pictures, which had a big hit in January called “Texas Chainsaw 3D.” But I don’t think they’re...” and his voice trials off.

A few months later, I call Dave to make sure he's seen a info graphic in the Washington Post. It was in the midst of nonstop Malaysian Air coverage and the graphic was designed to give readers a sense of just how deep the remains of that airliner potentially are at rest. As a reader scrolls down through the graphic, he passes various milestones. At 555 feet would be the depth if you were to invert the Washington Monument. At 1,250 feet, the Empire State Building upside down. Keep going down and you’ll pass the test depth of a U.S. Seawolf sub (1,600 feet), the depth a giant squid can swim (2,600), and the point at which light can be still detected from the surface (3,280). Scroll further still, past the mile mark, then the two mile mark, past the point where there’s not very much of anything represented on the screen, and you’ll finally get to the remains of the Titanic at 12,500. You think to yourself, wow, this is deep. Now keep going further still, until the graphic comes to an end at 15,000 feet, the depth at which the pinger signals have been detected emanating from Flight 370 and where the pressure is a whopping 6,680 psi. For the reader it’s the end of the line, though my hands feel like they want to keep pushing the mouse down even more. There’s no wreckage of K-129 included in the illustration, no indication that a bunch of guys once went out to sea and came back with part of a submarine from a depth greater than anything shown in the graphic.

“Yeah,” Sharp says, fully aware he’s become historically invisible, “it would have been neat if they had something that went to 17,000 feet in there.

"Oh, well,” he says. At least he still has that coffee cup.

Originally published in Washingtonian, August, 2014.